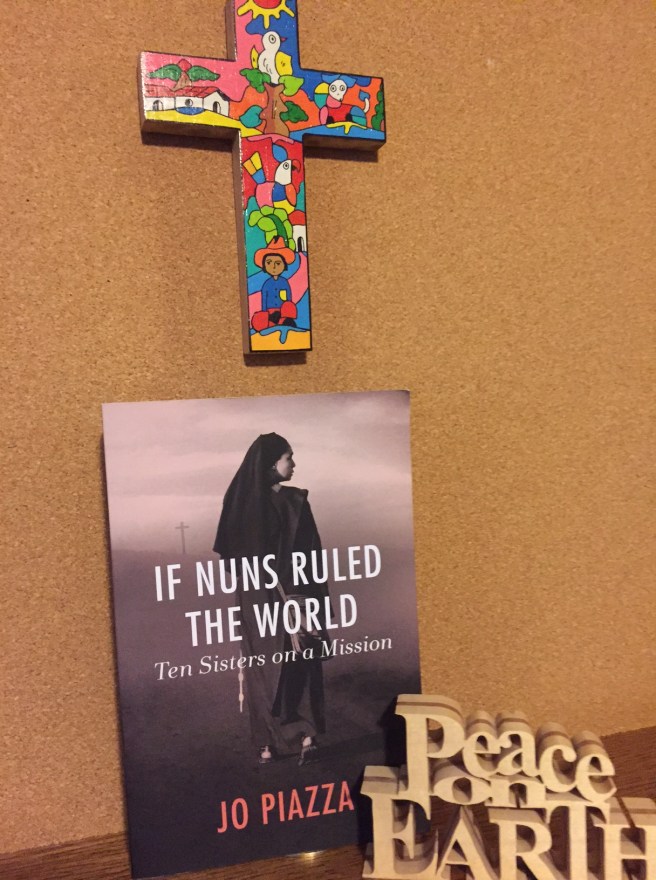

Forget what you think you know about nuns and the role of women in the Catholic Church. Jo Piazza’s If Nuns Ruled the World: Ten Sisters on a Mission serves up ten profiles in courage that will alter your perception of Catholic religious women. Leaders and activists, the American women Piazza profiles exemplify what it means to live out a commitment to social justice. Piazza shines a spotlight on the way each of these unique women carves out a niche within which she makes a remarkable contribution to the Church and the whole of American society.

To take one example, Sister Jeannine Gramick advocates for gay rights, including gay marriage. Often exposing herself to criticism and reprimands from other Catholic leaders, Sister Jeannine promotes dialogue, outreach, and advocacy for a more inclusive Church and society that embraces gay men and women in the totality of who they are in relationship to one another. The seedling of her calling to this mission grows from meeting a handsome gay man at a party one night. What then starts as a home ministry blossoms into a full-blown organization, and eventually multiple organizations. Sister Jeannine’s courage to promote gay rights and establish a connection to and from a Catholic community from which gay people have been alienated is, for her, all part of the Christian mission to bring God’s children together in love.

Sister Tesa Fitzgerald founded Hour Children to help women in prison connect with their children while they serve out their sentences. Sister Simone Campbell assumes the unenviable task of taking Catholic social justice issues to the sources of America political power. Meanwhile, Sister Nora Nash bellies up to power brokers of the corporate variety as an activist investor of sorts. What they all have in common is the capacity to defy any stereotypical or popularized version of what it means to live their vocation as religious women. They have chosen to model self-gift. By taking their individual gifts and gifting them back to a culture in which they often represent the counterculture, they have shown us a way of Christian living as old as Christianity itself.

As individuals working independently and as kindred spirits working collectively to shape a more inclusive America, the nuns profiled in this book give witness to living a contemplative life that is active in the world. They are examples of modern heroism and evidence of the spiritual riches that come from meaningful work. They may not generate the kind of wealth that accrues on balance sheets, but the value they create and the dividends they generate grow the common good.